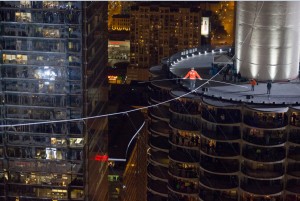

When Nik Wallenda traversed the tightrope high above Chicago last weekend, he carried a miniature HD cam and microwave transmitter to give viewers a look from his vantage to the ground below. (Photo: Courtesy Discovery.)

Tightrope walker Nik Wallenda may have pulled off the most spectacular thing happening last Sunday evening (Nov. 2) in Chicago with his breathtaking walk high above the Windy City, but running a close second had to be the ensemble of people and broadcast technology needed to produce television coverage of the spectacle for the Discovery Channel.

Peacock Productions, a production unit of NBC News specializing in live, long-form event coverage, produced Skyscraper Live with Nik Wallenda for Discovery Channel with the help of OB truck provider Game Creek Video, additional mobile facilities from Comcast SportsNet in Philadelphia and HD wireless camera specialist Broadcast Sports Inc., BSI.

Wallenda’s walk, a two-part effort with the first requiring an uphill climb at a 15-degree angle and the second a relatively level traverse –but blindfolded, thrilled TV audiences, Internet viewers and tens of thousands of onlookers in Chicago some 50 stories below.

Marc Weinstock, director of technical operations at Peacock Productions, spoke with me on the phone a few days after the event about what was required to produce the show and how it compared to the production of a previous Wallenda high-wire walk across the Grand Canyon, which Peacock Productions also did for the Discovery Channel.

Can you give me an overview of the live production resources deployed to cover the production of Skyscraper Live with Nik Wallenda for the Discovery Channel?

Sure. I would say it was a mix of some traditional broadcast, tried-and-true technology methods. For the main show, we used Game Creek Video’s Amazin truck with a fully functional B unit from them.

Then Comcast SportsNet, which is one of our partners in Philadelphia, provided the production truck for the digital backstage show.

That show had several cameras of its own, plus the backstage show took 10 of our ISO cameras and fed to the Web through some satellite technology. We used a six-channel MCPC [multiple channels per carrier] with Novelsat modulation and put up about 100Mbits on the satellite.

They took that down in Denver at Origin Digital and passed it on to Akamai so they could provide their six feeds to the Web.

BISS encryption and the use of Noble Sat modulators as well as fiber optic transport made it difficult for any unauthorized recording of the live event, says Marc Weinstock, director of technical operations at Peacock Productions (Photo: Courtesy Discovery.)

What about the production for television?

The main show had 27 cameras, including those that came from the digital show, which were mostly traditional broadcast cameras. We did have several RF cameras, which again is tried-and-true broadcast technology, but used in a different and new way.

For example, we put microwave transmitters in the backs of two elevators and had them run over 60-some-odd stories so you could see live pictures of Nik [Wallenda] when he was in either elevator at the different buildings.

Nik himself wore a transmitter and body-mounted camera, which provided those stunning pictures when he was up over the wire.

I would say [that was] newer technology with smaller cameras paired with tried-and-true, tested technology as well.

BSI, otherwise known as Broadcast Sports Inc., did all of the RF. We had a decent number of wireless cameras: the camera Nik wore, our Steadicam, which was pretty much everywhere, the helicopter, the two elevator cameras. We had a camera over at the Wyndham Hotel that was wireless. So they had their hands full. Plus all of this wireless communications –wireless microphones, IFBs, PLs and so on.

A total of 27 HD cameras captured Nik Wallenda’s feat for the main Discovery Channel broadcast. (Photo: Courtesy Discovery.)

You must have worked closely with the local SBE frequency coordinator in Chicago.

Very early on we engaged the local SBE coordinator and determined there was limited availability for what we needed and wanted to do for the amount of communications we were looking to put up.

So BSI partnered with the FCC and filed the appropriate STA [Special Temporary Authority applications] to get an unused TV channel in the Chicago TV market opened up. That was a huge piece of what we did because that allowed for us to have a plentiful number of channels for clear communications.

So there was no use of IP wireless newsgathering systems?

No. Those discussions were held early on, and if it had been something we needed to do, we would have done that. But since we were in a condensed operating area, those tried-and-true methods were the better options for us because we were able to receive them.

We were in close enough proximity. Had we gone into a larger area where we couldn’t really centralize all of our communications and cameras, perhaps that would have been brought up. But in this case, that wasn’t needed.

Since you brought up mobile IP-based technologies, I wanted to say those are great technologies, and we use them quite a bit in the news world as you already know. But in this case -where we had more than 65,000 people in one area- the cellular networks become absolutely trashed.

Most people had sporadic cell service. They couldn’t get data feeds out; they couldn’t upload pictures. So certainly in a production of this size with the expectations that we all had for it, “We can’t connect” is totally unacceptable.

That’s another reason we decided to go with tried-and-true microwave technology for those feeds because it wouldn’t be acceptable to have, “Oh we can’t connect now. Maybe we’ll get back to Nik when he’s on the wire.”

That’s a big reason why we went with some of these methods.

Simulations of the high-wire microwave link were used before the event to guarantee they would work once Nik Wallenda started his performance. (Photo: Courtesy Discovery.)

Can you tell me about how the program delay was set up to prevent live video from airing in the event of a catastrophe?

I am not exactly sure what items were used because that happened at the Discovery Channel in Sterling, Va. But what I can say is that from our site we either used direct point-to-point fiber optics circuits, or in the case of our uplinks –all were BISS [Basic Interoperable Scrambling System) encrypted.

So we used BISS encryption technology on the Ericsson encoders as well as using Novelsat modulators, which not a lot of people have either. We felt that approach provided multiple levels of encryption so people couldn’t accidentally end up recording the feed.

Has Peacock Productions been involved in producing any of Wallenda’s other recent high-profile, high-wire walks?

This is our second. We were the production team involved withSkywire Live, which was the one when he crossed the Grand Canyon, and that presented its own extreme challenges and difficulties that were entirely different. I think many of us left there thinking, “Wow, if we can accomplish this, we can accomplish anything." Which is true.

But I would say Chicago proved to be extremely, extremely different. I think many people, including me, might have thought it was going to be easier because now you are in a major metropolitan area and you can get the things you need. And that actually proved helpful.

However, it also brings along its own set of challenges. Out in the desert, you can do a lot of things that nobody cares about. But in the city of Chicago, you really can’t just put a truck somewhere and put a cone two extra feet out because you need the room. That’s not OK.

Whereas in the desert, if we have another truck, we’d just put it out there.

I would guess it was easier to get spectrum for your communications needs in the desert.

Yes, frequencies were easier to come by in the desert. But because of our filing of the STAs in Chicago, we really had a nice clean channel. Actually radio communications were better in Chicago than in the canyon.

Marc Weinstock, director of technical operations at Peacock Productions, says lessons learned from the production of Nik Wallenda’s tightrope walk across the Grand Canyon, particularly about the ability of fiber optic cable to stand up to the wind and elements, helped to shape production decisions about the most recent show.

Were there any lessons from the Grand Canyon walk that you took back to Chicago for this event?

Absolutely there were things that were learned. In the Grand Canyon, Nik wore two cameras on his body –one looking forward and one looking down. I think after the director saw that he said, “We don’t need that camera looking forward; we have that angle, and it’s not necessary.”

And I think there were several other camera angles where we said, “This doesn’t really buy us anything, let’s cut this or cut that.”

And then we added in [camera angles in] other places for our Chicago coverage so people had plenty of views.

Another thing we did in the canyon was the starting line was very far away on an island, technically. And we ran fiber optic cable over there and microwave backup because we didn’t know. Maybe the fiber would break.

But the lessons we learned were the fiber was very durable and held up very well. It held up in the high winds and the rigging that we put on it was very strong. So when we went to Chicago, we put out over 10,000 feet of fiber as primary and backup. But we did not feel the need to put up extra microwave backups because we learned that fiber could withstand the high wind.

It was really put to the test on Friday in those 60 mph winds. Everything held, and when we pulled it out and examined it [after the event], other than some discoloration, everything looked the way it did when we put it in.

Where was the fiber?

We had 10,000 feet of fiber running from the bottom of Dearborn Street where our TV trucks were, up the side of Marina Tower, around the back and then across from Marina East to the Leo Burnett Building. And we had left a significant sag in it so it wouldn’t obstruct people’s view of the walk.

It had its own rope across and that’s how we kept everything connected. That was the lifeblood of the whole operation.

Were there any other unusual or unique components to this production?

Obviously, one of the things that is hard to do is test how things are going to work in the middle of a wire in the middle of a city because, I would imagine, none of us are going to get out there and test it. And even if we had someone brave enough to want to do it, they don’t put the wire up until a day or two before the walk.

So you kind of have to do your best guess, best calculations, simulations. Again, working with frequency coordinators to make sure everything is where it should be so that when he gets out there is no problem.